The world is slowly recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. But the blow it struck to the rule of law remains persistent and widespread, according to fresh survey data collected in 140 countries. While declines in performance were not as extreme as in 2021, this year’s findings from the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index underscore the alarming drops in nearly every rule of law factor measured, especially in fundamental rights and checks and balances, which are two critical pillars of the rule of law.

Overall, these trends toward authoritarianism and away from rules-based liberal democracy portend dark trouble ahead. As big-power geopolitical competition continues to heat up, the differences in how states govern themselves will have outsized influence in shaping solutions to some of our most intractable problems – digital disruption and disinformation, corruption and illicit trafficking, and outright war. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, and its sophisticated disinformation tactics, shows just how dangerous this divergence has become.

Global trends – negative, with some exceptions

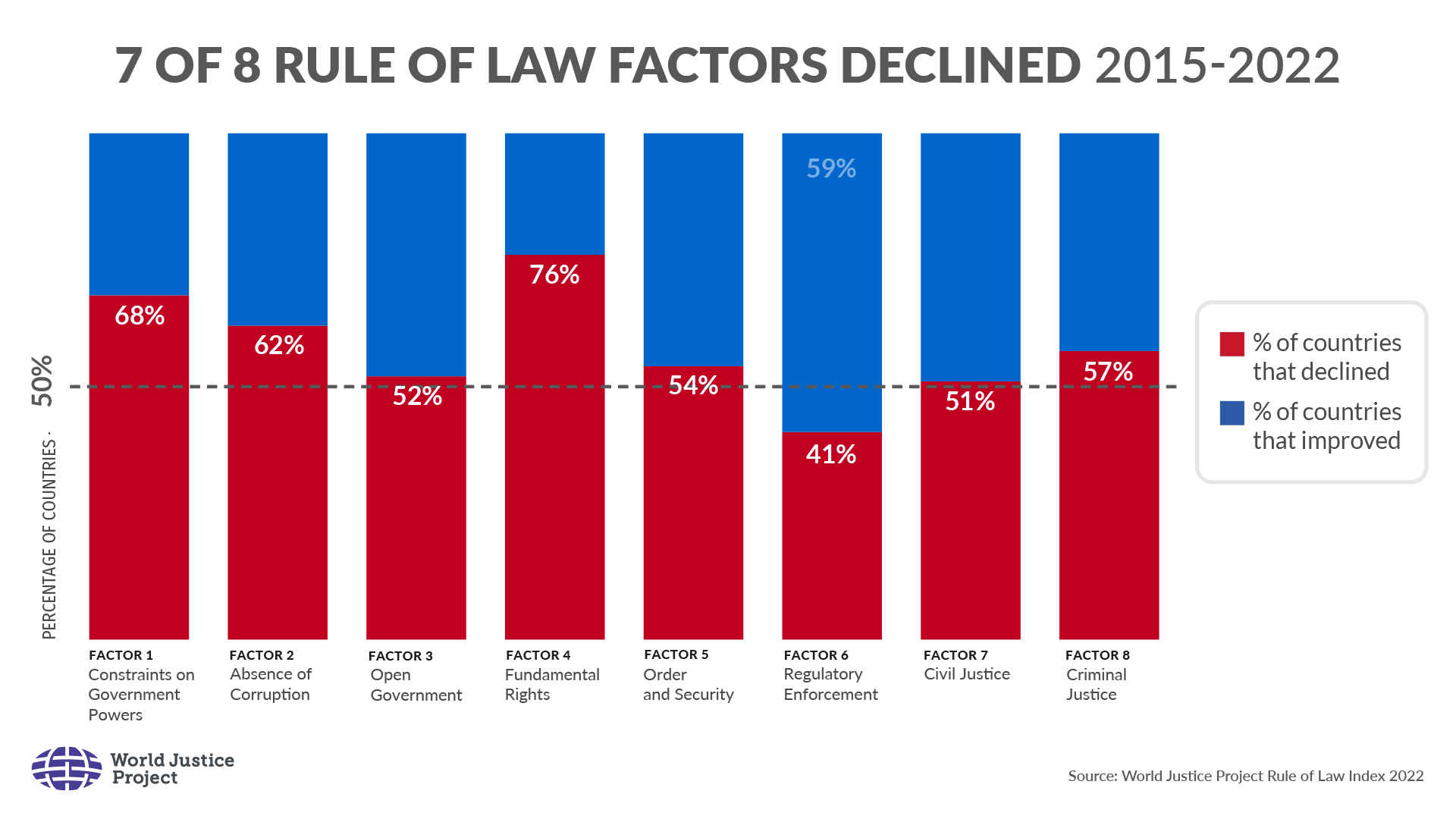

Around the world, the rule of law, as measured by eight factors – ranging from constraints on government power and open government, to fair justice systems and order and security – has entered its fifth straight year of recession. These negative trends, based on surveys in which over 157,000 legal experts and households report their experiences and perceptions of rule of law practices in their respective countries, have been driven mainly by growing authoritarian tendencies, such as weaker checks and balances, rising impunity, and an erosion of fundamental rights.

Freedoms of expression and association, the lifeblood of democratic decision-making, have been particularly hard hit, with declines in over 80% of countries surveyed since 2015. The transfer of political power in accordance with the law, which includes perceptions of the legality, integrity, and public scrutiny of electoral processes, also fell in two-thirds of surveyed countries during this time period. The intensifying competition for securing control of government is getting nastier by the year, with media, minorities, and dissidents in the crosshairs. Where power is unfairly or violently seized, as in Sudan, Haiti, and Myanmar, the rule of law is badly damaged and civil conflict worsens; where elections are open and peaceful, the rule of law rebounds, as in Honduras and, slowly and with some difficulty, the United States.

Europe, and its neighbors, continue to improve

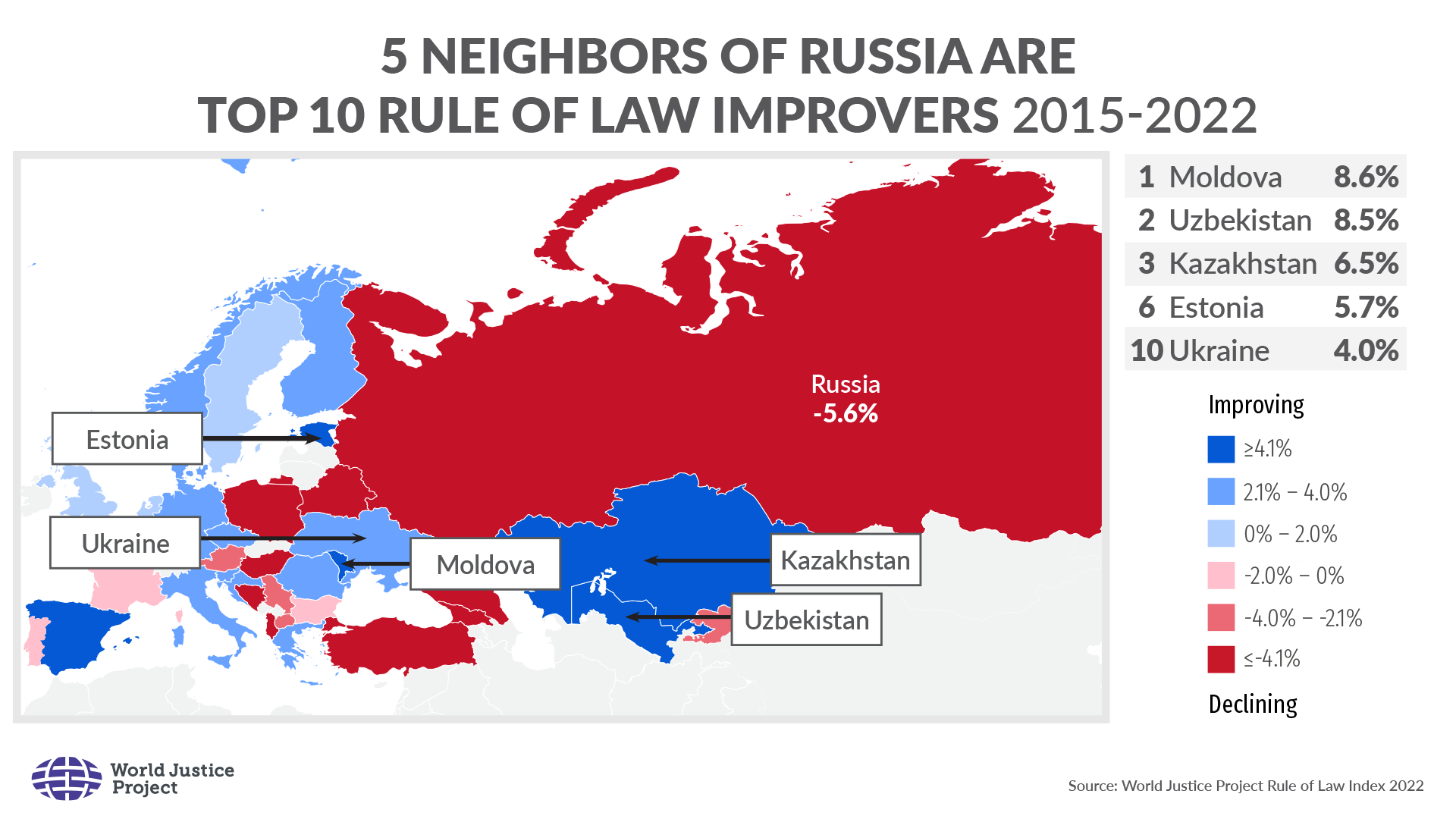

The big exception to these negative global trends is Europe, where nine of this year’s top ten rule of law performers can be found. Historically a strong performer, the region also continues to improve at higher rates than anywhere else, with over one-half of the index’s top 25 improvers globally since 2015. The construction of a Europe “whole and free” continues apace, built on a foundation of rule of law, human rights, and democracy, with notably strong scores on judicial integrity, open government, and fair regulatory enforcement. Newer European Union (EU) members like Estonia and Lithuania are making consistent gains; Romania and Bulgaria, though still lagging, also bumped up this year. And EU accession candidates Moldova and Kosovo were among 2022’s top five improvers globally, adding some wind in their sails for EU membership, which requires strict adherence to rule of law norms.

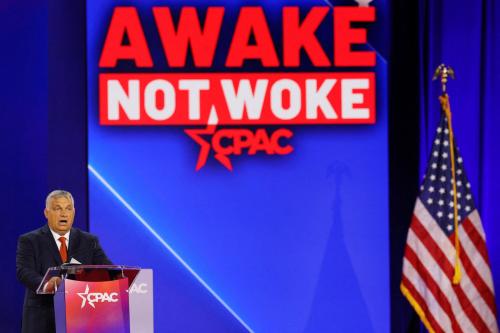

Despite bouncing back better than other regions from the rule of law backsliding induced by the pandemic, Europe is still suffering important long-term declines in such areas as discrimination, freedom of assembly, and lawful transitions of power. Notorious cases like Poland and Hungary, where rule of law scores have fallen around ten percent since 2015, validate why EU authorities are finally drawing the line. Brussels is enforcing its members’ own treaty obligations to demand course corrections or pay a hefty penalty, as Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán faces now. EU neighbors Turkey, Georgia, and Bosnia also exhibit significant multi-year declines.

The steady improvement in rule of law practices experienced in most of Europe is now reaching more states on its eastern flank. This includes several next-door neighbors of a revanchist Russia and its cousin Belarus, two states that rank among the biggest decliners since 2015. Reform-minded regimes in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, for example, are among the top ten improvers globally in their rule of law performance since 2015; meanwhile Russia and Belarus continue to fall in the opposite direction. Not surprisingly, Ukraine’s score fell in 2022 after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s military invaded the country, but over time it has demonstrated some improvements in fundamental rights, order and security, and regulatory enforcement. Its ability to turn back Russian forces and return to the path of democratization, especially the fight against entrenched corruption, will determine its chances of joining the EU anytime soon.

China and India – a race to the bottom?

Two other rising powers with very different governing systems nonetheless share some worrying traits when it comes to rule of law. China, which the index ranked 95 out of 140 states, and India, at 77, are virtually tied in their respective declines in rule of law scores since 2015, by -1.6% and -1.7% respectively. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s successful consolidation of China’s Communist Party leadership this month, now with even fewer checks on his power, portends even weaker rule of law adherence in the future. Beijing’s strong-arm crackdown against peaceful protesters and the media in Hong Kong, which has fallen five years in a row on its rule of law score, is further evidence of a China that is closing ranks against any internal challenges to its one-party rule. This likely increases the chances of more aggressive behavior against its perceived rivals, as well as a democratizing Taiwan.

Meanwhile India, the world’s largest democracy, once had an encouraging trajectory toward more open government and robust public debate, but no more. Since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi consolidated his power at the helm, India’s rule of law performance has declined markedly in criminal justice (-17.7%), fundamental rights (-12.8%), and checks and balances (-6.3%). Falling scores on the integrity of police and military officials, freedoms of religion and expression (particularly targeted against Muslim minorities and around disputed claims in Kashmir), and non-discrimination drove the erosion, despite some improvements in administrative due process, accessibility of civil justice, and legislative branch corruption. But because it is increasingly aligned with its Indo-Pacific partners as a security check against China’s ambitions, New Delhi largely has gotten a pass on these alarming trends.

The United States slowly rebalances after Trump

Once a self-proclaimed champion on rule of law around the world, the United States fell five years in a row under former U.S. President Donald Trump’s presidency. In 2022 it recovered its footing, increasing in all eight factors measured by the index. Compared to 2015, however, it still is underwater on such key pillars as checks and balances, accountability for official misconduct, and lawful transitions of power. Its abysmally low global ranking on discrimination in both the civil and criminal justice systems (121 and 106, respectively) is embarrassing. To his credit, U.S. President Joe Biden has tried to thread the needle to restore some of Washington’s credibility as a leading democracy, at home and abroad, as demonstrated by his robust defense of Ukraine, his new national security strategy focused on the threat of a menacing and anti-democratic China, and his Summit for Democracy initiative. But much more work needs to be done by all concerned to put the United States on a better course for the future.

Washington must also contend with a deteriorating security and rule of law situation on its southern border: Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti figure in the bottom ten countries for rule of law globally, generating millions of migrants to the United States and the region. Brazil, mostly under Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s watch, has declined five years in a row. And countries like Bolivia, El Salvador, Mexico, and Colombia remain declining performers in key governance areas such as control of corruption, criminal justice, and order and security.

In sum, global trends toward and away from rules-based and rights-respecting governance are increasingly matching up with the fault lines of intensifying geopolitical competition around the globe. The multipolar world at our doorstep is not only messy, volatile, and insecure; it also raises existential questions of how power is shared and human dignity is protected. To prevent the next big titanic clash, the United States, Europe, and its other like-minded allies will need smart strategies both to shore up their own performance as open and just societies and to defend vigorously those values abroad.

Commentary

Rule of law continues five-year decline, but bright spots emerge

October 31, 2022